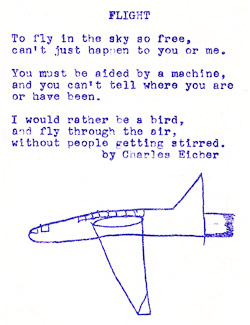

I was delving deep into my archives for some old records, and I found the oldest piece of personal artwork I know of, a poem and drawing I made when I was 10 years old. I can find nothing I created that is any older than this little scrap of paper. It’s a pale purple mimeograph, I vaguely recall this was from a class assignment to write a little poetry magazine. I was always scribbling little pads full of paper with airplanes on them, I was crazy about airplanes when I was a little kid. The teacher traced my drawing onto the mimeograph stencil, I’m sure she missed tracing half the tail, I certainly would not have omitted such a crucial detail.

Category: Art

Stereoscopic Computer Graphics Circa 1992

I haven’t posted anything for a while, and at times like this I like to hunt around for some old work in my archives. So here’s a computer graphics project from 1992 that I’m rather proud of. It is deceptively simple, but that is part of any artist’s repertoire, to make the difficult things seem simple.

I was first introduced to stereograms when I was a young child, my family would visit my Grandmother and she would always bring out her Victorian era stereogram viewer and old stereo photo cards showing exotic sights from around the world. Perhaps this was a bit ironic since my Grandmother was totally blind. She became blind as an adult, so perhaps she was sharing the same images she viewed as a child.

I learned to draw stereograms by hand in a perspective drawing class in my first year of art school, an arcane procedure that confounded most drawing students, but I enjoyed it immensely. Each year, a collector of stereograms came to the art building and set up a stall to sell individual stereo photo cards, I used to spend hours looking through his collection, but since I was a starving artist, I never had enough money to buy any of them. When I first got access to 3D computer graphics hardware in art school, my first project was to produce stereograms. Unfortunately, the hardware was primitive and low resolution, and the depth effects were difficult to perceive. I remember how difficult it was to get my professor to come over to the art school and see my first stereograms, since the only graphics terminals were in the Computer Science building, and artists of that time wanted nothing to do with computers. I finally managed to get him to come over for a demo, I produced stereograms of bright arcs swooping through space, an homage to a famous sculpture by Alexsandr Rodchenko. The professor devastated me with the remark “oh, that’s just technical.” That was when I decided to drop out of art school. It would be 15 years before that professor jumped on the bandwagon, and tried to make his reputation as a guru of 3D Virtual Reality. And of course, by then he had completely forgotten that I was the first artist to ever show him a stereoscopic VR image.

After dropping out of art school, it would be amost 10 years before I could afford my own computer equipment capable of rendering stereograms. I did some primitive stereoscopy experiments with Paracomp Swivel 3D, but the first application capable of doing the job properly was Specular Infini-D. One of the demo images in the Infini-D application was an animation called “virtual gear.” I viewed it and was immediately irritated, it was just a disk spinning on its axis, not a gear at all.

Now if you’re going to call your demo “virtual gear,” you have a historic precedent to live up to. One of the most famous interactive computer graphics experiments of all time was Dr. Ivan Sutherland’s Virtual Gears. Sutherland set up an interactive graphics display showing two gears, you could grab one gear with a light pen and rotate it, and the second gear would move, meshing teeth with the first, moving as perfectly as real gears would.

Gears are a graphics cliche that annoys me continually. Gears are overused as an iconic image, and are almost always badly designed. I can’t count how many times I’ve seen animated gears that would not work in reality. The gears don’t mesh, or are combined in mechanisms that would jam. I’ve even seen gears that counterrotate against each other, if they were real gears, all the gear teeth would be stripped away.

My Grandfather was an amazing tinkerer, and was always constructing clever little gadgets with gears and pulleys. My favorite gift from my Grandfather is a college textbook from the late 19th century entitled “Principles of Mechanism.” The book shows how to design gear and pulley mechanisms, and shows how to distribute power throughout an entire factory from a single-shaft waterwheel. I always enjoyed the strange diagrams and mechanisms, and was astonished how much advanced calculus went into the design of even simple gear teeth. So when I saw the Infini-D image, I immediately thought back to “Principles of Mechanism” and decided I could do better. I would design a properly meshing set of gears that was accurately based on real physics. To make it a challenge, I would make the gears different diameters with a gear ratio other than 1:1. And to add realism, I would produce it as a ray-traced 3D animation. Click on the image below to see the finished animation pop up in a new window.

In order to design the gears properly, I had to sit down and work through quite a bit of the physics of gear design. I discovered some interesting things about gear ratios, if I designed two different diameter gears with the right ratio of teeth, both gears would return to a symmetric position after only a half rotation of the largest gear. This would allow me to produce a fully rotating animation loop without having to animate the full rotation, I could just loop the same frames twice, saving half the rendering time. Look closely at the animation, the slots in the two gears match up after the left gear rotates only 180 degrees. There are 60 frames in this animation, but it takes 120 frames to complete one full cycle. I saved 50% of the rendering time.

And it was good thing I discovered this trick, the animation took 48 hours to render on my Macintosh IIcx. I borrowed a Radius 68040 coprocessor board and the animation rendered in about 24 hours. When I bought a new PowerMac 8100/110, the render took about 20 minutes. I haven’t benchmarked this file since then, but I suspect it would render in about 30 seconds on my current dual 1Ghz G4 computer (if I could get Infini-D to run at all).

My stereoscopic rigging in Infini-D took months of fine tuning to get it to work perfectly. About that time, Specular Inc. started releasing inexpensive accessory packs for Infini-D, selling for about $100. I had previously contributed some work to Specular, producing a procedural texture generator for cloudy skies, the “Sky Library” which you see in the background of this stereogram. Sky Library was Specular’s most popular software download, and they knew of me and my work, so I started negotiating with them to sell my camera rigging as a software accessory pack, with an inexpensive plastic stereogram viewer included. I sent them several animated stereographic demos including Virtual Gears, high-resolution Iris inkjet printouts of various stereograms (which were very expensive to produce in 1992), and a freestanding stereo viewer. They had never seen stereograms and did not understand how the viewer worked, they tried to hang the metal legs over their ears, so I sent them a videotape showing how it stood up on the metal legs. I worked for months, trying to get their interest in releasing my work as a product, but they told me there was no market for my rigging, and they didn’t want to release it. I persisted, but eventually they stopped returning my calls.

A few weeks later, I received a mailing of the Specular Infini-D users’ newsletter, and was astonished at what I found. The newsletter’s feature article was about setting up stereographic camera rigging in Infini-D. The article used all the methods I had taught them, but the setup was all wrong. They had taken all my careful design, published the core concepts, but missed all the mathematical subtleties that made the images work as a stereogram. And to add insult to injury, I did not get any credit at all, they claimed they invented it all by themselves.

How To Look At Art

One of the most impressive art exhibits I ever saw was a massive Ad Reinhardt retrospective at the LA Museum of Contemporary Art in 1991. Reinhardt is considered one of the most influential artists of his time, and famous (as well as infamous) for his radical Minimalist artworks. It was amazing seeing the development of his work over his career, first with brightly colored, playful paintings, gradually shifting to his famous “black on black” minimalist works. But I was absolutely stopped in my tracks when I entered a gallery containing some of his final works, monumental black paintings.

I had heard of these paintings before but had never seen one firsthand, and now here was an entire room full, exhibited in pairs as the artist intended, each painting about 6 feet wide and 12 feet tall. The LA MOCA galleries are beautiful tall white rooms with blond wood floors, and scattered about are black leather minimalist couches by Mies van der Rohe, echoing the black paintings like little black clouds floating off the ground. It was the perfect setting to contemplate the paintings, so I sat down and slowly gazed at the paintings, trying to absorb every impression I could.

As I sat in the gallery, staring at a particular pair of paintings, a man walked by and gave me the most curious look. He stood to one side of me, looking at the paintings, and then watched me for a moment. Then he timidly walked up to me, and asked me, “excuse me, if you don’t mind me asking, what are you looking at for so long? These are nothing but black paintings.” I said “oh no, these aren’t just black paintings, why don’t you sit down here and look at them with me, and I’ll tell you all about them.”

We must have been quite a pair sitting there, a scruffy young artist in my black painter’s pants and leather jacket, and the barrel-chested middle aged man in a plaid work shirt and khaki pants with red suspenders. I told him, “look slowly at the paintings, they are far more complex than they seem with just a quick glance. Ad Reinhardt was a fanatic about technique, and these paintings aren’t just a coat of black paint on canvas, they are actually quite complex. Reinhardt ground his own pigments and made his own paint to precise specifications, and applied dozens of thin layers of paint to get the precise effect he wanted. Sometimes there are layers of color underneath a black layer, he used a whole range of colors in his black paintings. Light penetrates into the paint and reflects back out with a color cast that can’t be seen except by slowly viewing the painting. If you look at the paintings for a minute or so, you can see a faint glow of color in the black. Sometimes you can see color around the edges of the painting, like an aura. The artist intended for you to get the impression of a color without actually seeing any colored objects. Can you see the color in these paintings? Tell me, what colors are they?”

He looked at the paintings silently for a moment, and then said, “yes, I can see it now, the one on the left is red and the one on the right is blue.” I said that was the same thing I saw, and each of the pairs of paintings had a similar set of contrasting colors. He said he couldn’t believe it, he thought these were just black paintings but they really were interesting to look at.

The man thanked me and said he was glad I’d explained it to him. And I told him I was glad he enjoyed the paintings. He got up and walked around the gallery, and slowly looked at each pair of paintings, with a contemplative look on his face.

One of the reasons I like Ad Reinhardt’s minimalist black paintings is that you must sit and look at the original works, they can never be reproduced in another medium. No photograph of the paintings can ever substitute for sitting there in front of the original. I describe viewing these works as a “pilgrimage,” you go to see the painting firsthand because there is no other way to get that experience. I’ve always tried to use that effect in my own work, particularly my abstract prints, which use elaborate metallic and irridescent pigment effects that can only be seen in the original, and use whole ranges of “black color.” Unfortunately, that makes it impossible to show my best artworks on the internet, or even as a photographic reproduction or a slide. This also makes it particularly difficult for me to get an art gallery interested in selling my works. Most galleries select artists by viewing slides of their work. I wonder how successful Ad Reinhardt would have been, if he had to submit slides of his black paintings to galleries.

Dutch Blue

A few years ago I took a seminar in ukiyo-e history at my art school. One of the other students, a Chinese woman, was the star of the class, she had an MA in Art History from Beijing University and was working on a PhD. She always knew how to read all the obscure kanji seals, which was a delight to everyone, especially the professor. She spent an entire semester investigating one strange question, I tried to help her research it, but we never could find an answer. But oddly enough, this morning I turned on the TV and NHK had a 30 minute documentary about this very subject: Dutch Blue.

In Japan, a particularly intense color known as Dutch Blue or Delft Blue, is well known for its common use in ukiyo-e printmaking. But the question was posed, what is Dutch Blue, what is its chemical composition and where did it come from? Did it come from the Netherlands? We never could find out the answer.

But today’s art history lecture on NHK was about Dutch and Flemish painting. Apparently the famous Vermeer painting “Girl with a Pearl Earring” is on display in Tokyo, and it has caused the same sensation that accompanies it everywhere it is displayed. Could the blue scarf the girl is wearing be the same Dutch Blue?

Indeed it is, but not for the reasons you might think. The NHK crew visits a traditional Dutch paint maker, and we see his ancient methods. He even lives in a windmill, using the wind-driven millstones to grind mineral pigments. But Dutch Blue is too precious to mass produce, so we see his hand-grinding apparatus, a tall copper pestle with a long shafted mortar. The paintmaker retrieves a chunk of bright blue mineral from his shelf, and at last we see what Dutch Blue is composed of: Lapis Lazuli.

Lapis is a semiprecious stone, almost the entire world’s supply comes from Afghanistan and Iraq. Dutch traders brought the mineral to Europe and it was used in oil painting during the Renaissance, but due to its expense, was too precious for everyday use. But thinly applied and mixed with white, bright, luminous blue skies became a hallmark of Flemish landscape painting.

But in European painting, this color is known as ultramarine, and if the color really had come to Japan through European traders, it would probably be known by another name. That is the most interesting part of this story.

Dutch Blue is a misnomer. According to the documentary, Dutch Blue first came into widespread knowledge in Japan on imported Chinese porcelain. Most people are familiar with Ming era ceramics and their bright blue painted markings. The color really should be known as Ming Blue. But Ming Blue is not made from Lapis Lazuli, it is cobalt oxide, even though the color is extremely close to Dutch Blue.

By a historical coincidence, Ming ceramics were first imported to Japan at the same time Dutch traders came to Japan. Dutch trade goods were wildly popular, and the Ming Blue color became associated with the Dutch goods. Real Delft pottery with the distinctive cobalt blue color would not be made in Europe for nearly a hundred years after the glaze was discovered by Chinese ceramicists.

The question still remains, how did the Lapis Lazuli come to Japan? Perhaps it was brought by Dutch traders, I didn’t hear anything about that in this documentary. Most water-based pigments used in nihon-ga and ukiyo-e are mineral pigments, and we now know that finely powdered Lapis Lazuli was used in these Japanese artworks. But at least now we know how Dutch Blue got its name.

Photography for the Blind

When I was just a young art student, I looked through a catalog of photography seminars and found something astonishing, a class called “Photography for the Blind.” I never heard anything so outrageous, how could blind people do photography? So I read about the class, and it described an idea so radical that I’ve never forgotten it.

Of course someone who is totally blind cannot see or take photos. But there are far more people who are partially blind rather than completely sightless. Nowadays we call this “low vision” or “vision impairment,” but this covers a wide variety of vision defects. Many people with low vision cannot see objects more distant than a few inches, or only see objects obliquely with their peripheral vision, but these people can see photographs if they view them under the right conditions.

I was particularly struck by the story of one student. She had could not see distant objects, but she could read books if she held them about an inch from her eyes. The school gave her a point-and-shoot Instamatic camera, and taught her how to aim the camera without using the viewfinder. The school processed the film and made extremely enlarged prints. She produced a lot of crooked, badly cropped photos, but overall, they weren’t too bad for someone who couldn’t see what she was doing. But the whole point of the class wasn’t to make fine art for the general public, it was intended to make personal artworks just for the student’s own personal enjoyment. And this woman described her feelings when she saw photographs of her friends’ faces, allowing her for the first time to see what they looked like. Special photographic techniques are often used to capture images of things no human eyes could see, but I never imagined photography could allow the blind to clearly see the world around them for the first time.

Painting 101

I took a short break right in the middle my painting project, a series of distractions kept me from the easel right as I was feeling particularly productive. But part of the process of painting involves a lot of waiting, staring at what work you’ve already done, trying to absorb any lessons you’ve learned in the process, and decide what you’re going to do next. Some artists are particularly involved with the process of creating their artwork, even more than their involvement with the final results. This project is particularly focused on exposing the most intimate part of a painter’s work process.

As I began this project, I thought back to a major incident that occurred during my first painting class in art school, almost 30 years ago. I was a photography major, and there was considerable disdain for “modern” art media like photography, the Dean thought the art school should only teach painting, drawing, sculpture, and printmaking. Students from the upstart photography department were sure to face difficulties with the traditionalist painting professors. But now I had to do my painting coursework as part of the BFA degree requirement, so here I was in Painting 101.

Our painting professors had a unique approach to teaching, they decided to not teach anything. It was considered a bad idea for painting teachers to actually teach or demonstrate specific techniques, it was feared that the students would learn to paint exactly like their professors, instead of developing their own imagery and methods. The result was a lot of novice students fumbling around and not knowing what they were doing, producing a lot of bad paintings. And my work was as crappy as anyone’s. I mostly applied paint right out of the tube, nobody ever told me that you were supposed to mix colors and add white pigments, or that solvents like turpentine and oil were standard methods, in fact, that’s what makes it oil painting. Time in the studio was scarce, we only had 1 hour 3 times a week, and we were expected to come in 3 more hours a week, but the studios were always occupied with other classes, and we were at the bottom of rung of the ladder.

But of course, being the enterprising young technologically-oriented artist that I was, I decided I could study and improve my technique by applying other tools to painting, tools I was already familar with: photography. My idea was simple. I never had enough time in the studio to just look at my painting and see what I’d done. So I would take a instant photo of my painting at the end of each class, using my nifty new Polaroid SX-70 camera. I could carry around the instant photo and study it until I got back into the studio, 2 days later. I had previously done this in sculpture class, photographing my clay models from different angles to study lighting and form.

Of course this was the perfect way to invoke the antagonism between photographers and painters that had been going on for decades. My professor had a fit. He accused me of cheating, he reacted just as if I was copying from a photo, which was considered to be an evil technique used only by the worst, laziest painters. The professor also accused me of flaunting my expensive camera equipment in front of the other starving students, that I had an unfair advantage, the other students without cameras could not compete. I offered to take photos of any other students’ works for merely the cost of the film, about 75 cents each, the other students could have prints without having to own a camera. The professor liked that idea even less. I was immediately snubbed and subjected to the harshest sanctions by the professor, he gave me an F for the class. I would have to repeat Painting 101, but it was only taught in the fall semester. Instead of graduating that year, I would have to wait until next year before I could even begin my senior year’s work in art school, and I could not afford it. My painting professor had essentially kicked me out of art school. It took me 25 years to come back and finish my BFA degree. I had to take Painting 101 all over again, and I got an A.

This Art Stunt stop-frame experiment is the logical extension of my fiddling around with a Polaroid camera, recording my own works while in the process of creating them. And the ultimate irony is that in the last 20 years, a considerable body of art historical evidence was discovered, indicating that some of the greatest painters, held up as paragons of natural virtuosity in painting and draftsmanship, were cheating with lenses and cameras.

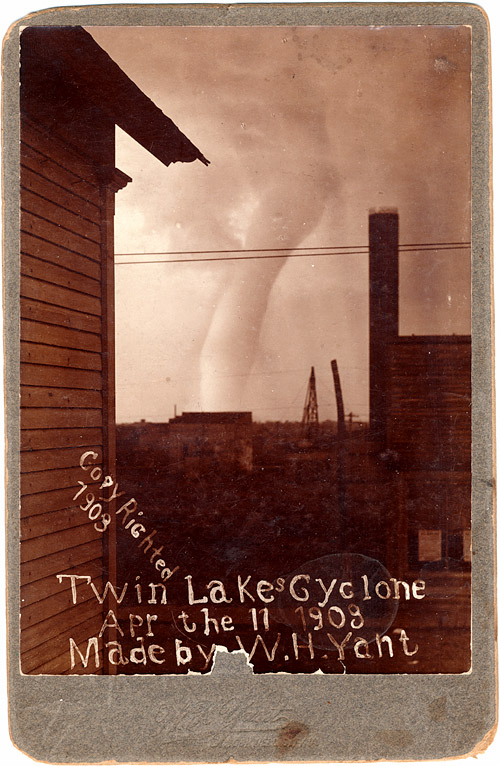

White Tornado

I’ve been going through my photo archives and pulling a few notable images, and this is one of my favorites. I don’t remember exactly how I got this card, it must have been when I was on vacation in Okoboji when I was a kid. I have a small collection of local weather-disaster photos but this is the best image I have, even if it is in a terrible state of preservation. As far as I can determine, this is the first image ever captured of a tornado. Up to this time, film was not fast enough to capture a moving tornado, even after the invention of fast film, it took a while for a lucky photographer to be in the right place with their bulky view camera equipment.

Even back to the early days of photography, there were stormchasers that mass-produced prints. Usually they came in the aftermath of the tornado and took photos of the devastated area, and sold stacks of prints to the locals as mementos.

Philip Guston

I was reading ArtNews today and saw a short article on the painter Philip Guston (unfortunately it is not available online). I saw one picture of Guston’s studio and burst out laughing, it reminded me of something..

When I finished my BFA in painting, I had to take a seniors seminar. I liked the teacher, but sharing this particular class with a mixed bag of undergrads was always dicey. When we weren’t savagely critiquing each other’s work, we usually watched videos. There were a couple of students who idolized Philip Guston so the teacher arranged for a viewing of a long documentary shot in Guston’s studio.

Our university has a rather nice Guston painting in its museum, and he’s a major influence in some circles in the painting school. Of course, like any artist, I am absolutely convinced my interpretation of Guston’s work is the correct one and all other points of view are absolutely incorrect. And my fellow students who loved Guston so much had the most egregiously incorrect interpretation I’d ever seen. I had to share a painting studio with one of them, he was always spewing out awful Guston pastiche paintings, and doing stupid stunts like spilling plaster everywhere, like on my still-wet oil paintings.

But anyway, these Guston devotees and I watched the film avidly. They excitedly discussed every detail, as Guston mixed colors and demonstrated his brushwork. The film spent about 30 minutes watching as the painting’s primary layer was executed, Guston discussed the imagery in this work, and then stopped work for the evening.

The film returns early the next morning and Guston is just setting up to paint again. But the huge canvas he’s worked on all yesterday is now blank. The filmmaker asks Guston what happened. Guston says, “I got up this morning, decided I hated it, so I scraped it down and wiped it all away with turpentine.” I suddenly burst out in uncontrollable laughter, I couldn’t stop myself. Guston was playing a monumental joke on his devotees who would be so stupid as to draw any interpretation of his work from the way he painted it. I laughed so hard, the teacher stopped the VCR and asked me what was so funny. I said, “we just learned precisely how Philip Guston does NOT paint.”

Gerhard Richter at the Art Institute of Chicago, Liz Larner at MCA

I just returned from the Gerhard Richter show at the Art Institute of Chicago, I haven’t seen such a fine exhibit in many years. I was astonished to learn The Lannan Foundation donated their entire collection of Richter paintings to the Art Institute. I caught several Richter showings at The Lannan Museum in Los Angeles, including the Baader-Meinhof exhibition. It has been a long time since I saw these paintings, and now they are collected and displayed with the most significant pieces of Richter’s entire history. I will definitely have more to say about this exhibit, and I will definitely be returning to see it again.

I was also rather pleased to see a large Liz Larner sculpture at the Museum of Contemporary Art. I had heard that her retrospective would be at MCA but I was disappointed to find that it was not, only the one piece was on display outside the museum. Liz was part of the LACE Gallery scene in the LA Loft district where I lived. I especially loved her kinetic sculpture displayed at LACE, it was titled “Corner Basher” but I always called it the “LACE Bashing Machine.”

It was a long vertical pole with a heavy chain and a steel ball attached at the end, it looked like a tetherball made from solid metal. A motor would spin the pole, you could control the speed of the motor with a big knob. At slow speeds the ball would arc lazily through the air, but at higher speeds, the ball would hurl around at terrifying speeds, the chain would rise, and the ball would slam against the walls of the museum. You could easily knock huge chunks of drywall and wood out of the museum walls, and in fact, you were invited to do so. The whole museum would shake with a reverberating BOOM whenever the ball hit the walls, and it hit repeatedly, with a repetitive thunderous noise about two times a second. I could tell the LACE staff was absolutely frazzled from the noise. I lived near LACE so I loved to drop in and bash it around, and see how far the damage had progressed. I think that was Liz’s last show at LACE.